The Caretaker of the Departed

A quick Google search on the toughest, craziest, and weirdest jobs on the planet will yield results such as oil rig worker, landmine remover, snake milker, sulphur miner, and more such trades, in no particular order. Somewhere in those results also appears the job of a mortician — one who prepares deceased people for funerals and interment by embalming and dressing them. It wouldn’t come as a surprise then, for more than one mortician to be affiliated with the Colón Cemetery, a 150-acre plot nesting over 800,000 graves in the heart of Havana.

©Ayash Basu. One of the over five hundred intricate mausoleums at the Colón Cemetery.

But this post is neither about the impressive 19th century cemetery nor its morticians. It is about a man, who for over the past decade or more, has been doing what comes after someone is buried at the Colón Cemetery. Three years after burial to be precise. Some context is in order at this point, so here goes a brief one. With over two million residents in Havana, land is obviously at a premium and the same extends to within the cemetery grounds. Hence, typically after three years, the remains are removed from graves and the contents stored away in smaller boxes. This frees up cemetery land, making it usable and rentable continuously, while the remains continue their “Carbon 14 isotope” half-life journey in smaller boxes stacked away at an underground crypt.

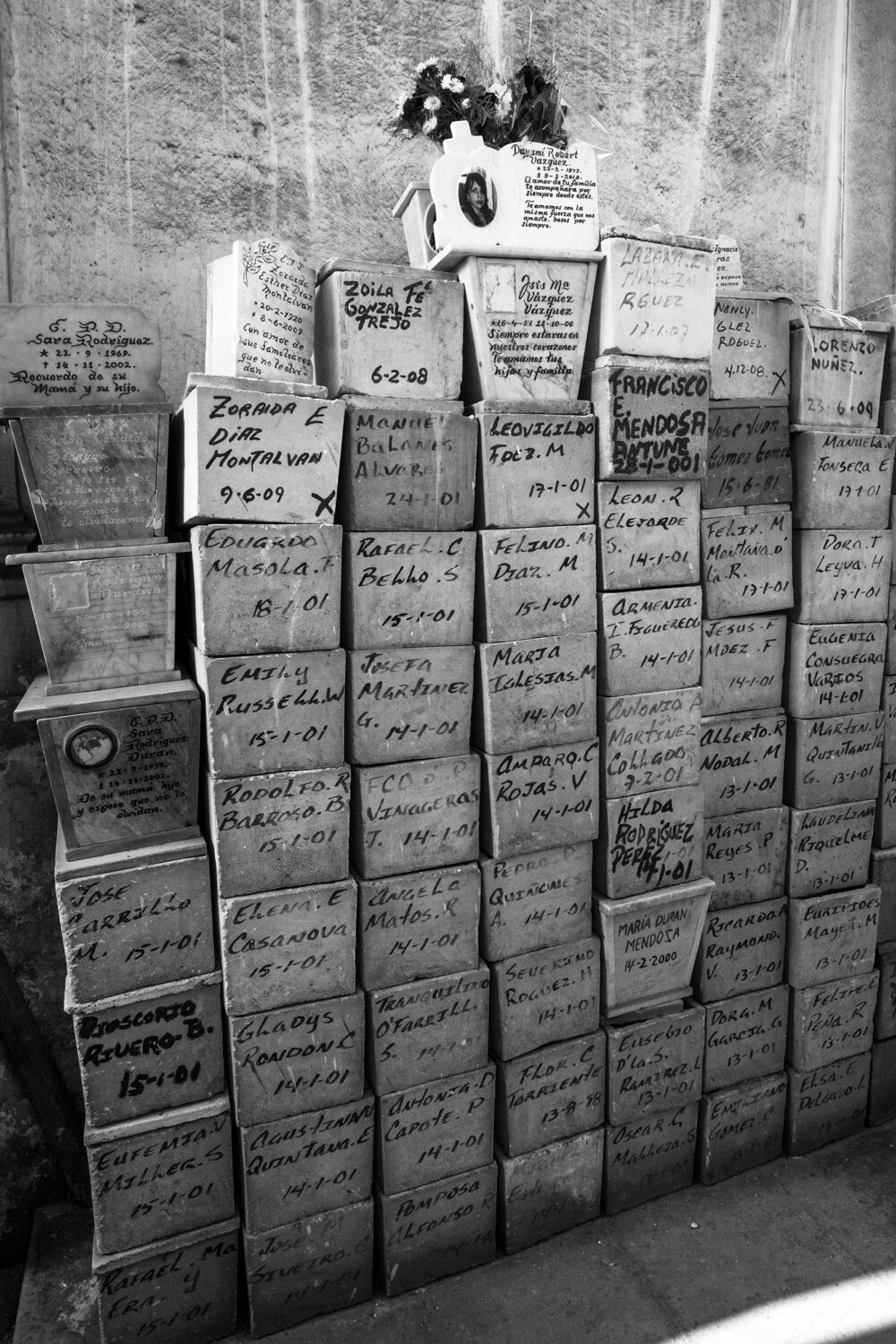

©Ayash Basu. Graves are dug up after three years and the remains carefully packed in small concrete boxes.

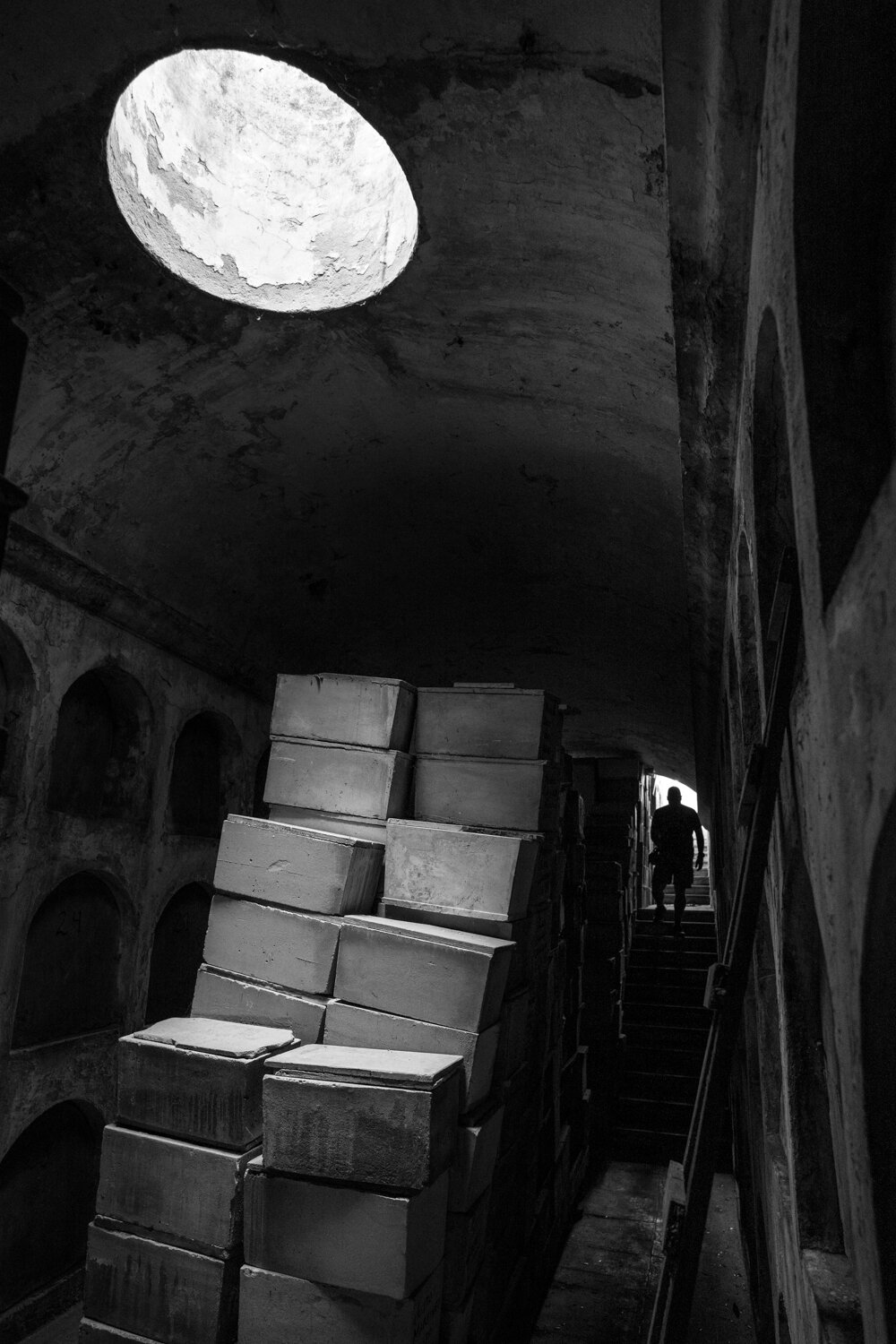

So, how does this really work and who does it all? One man, Carlos Sardiñas — a tall, lanky, and animated personality with a Cheshire grin, who commands the long, dark, damp, and eerie corridors of the catacombs underneath the Colón Cemetery. Sardiñas’s job description includes storing, cataloging, stacking, and caring for thousands of remains, some spanning generations of families—day after day. His “office” is underground, accessible by a narrow staircase, damp and musky, as rain water seeps in with every downpour. There are no lamps or bulbs, the only light source being the overhead skylights that run every thirty feet or so. Any wisp of fresh air can only be had all the way outside. To anybody who grudgingly moans for a silent and peaceful work space, I say, “careful what you wish for.”

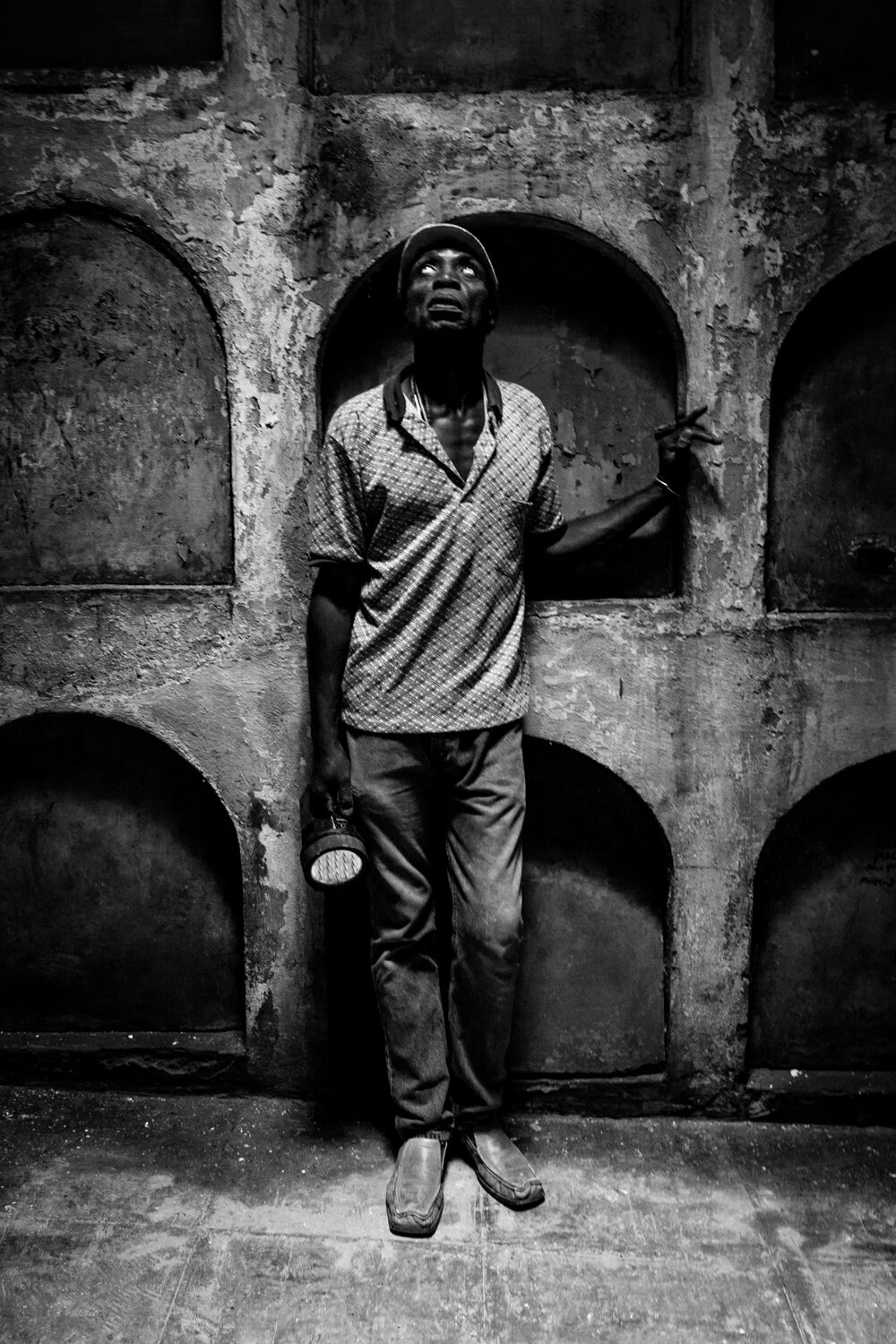

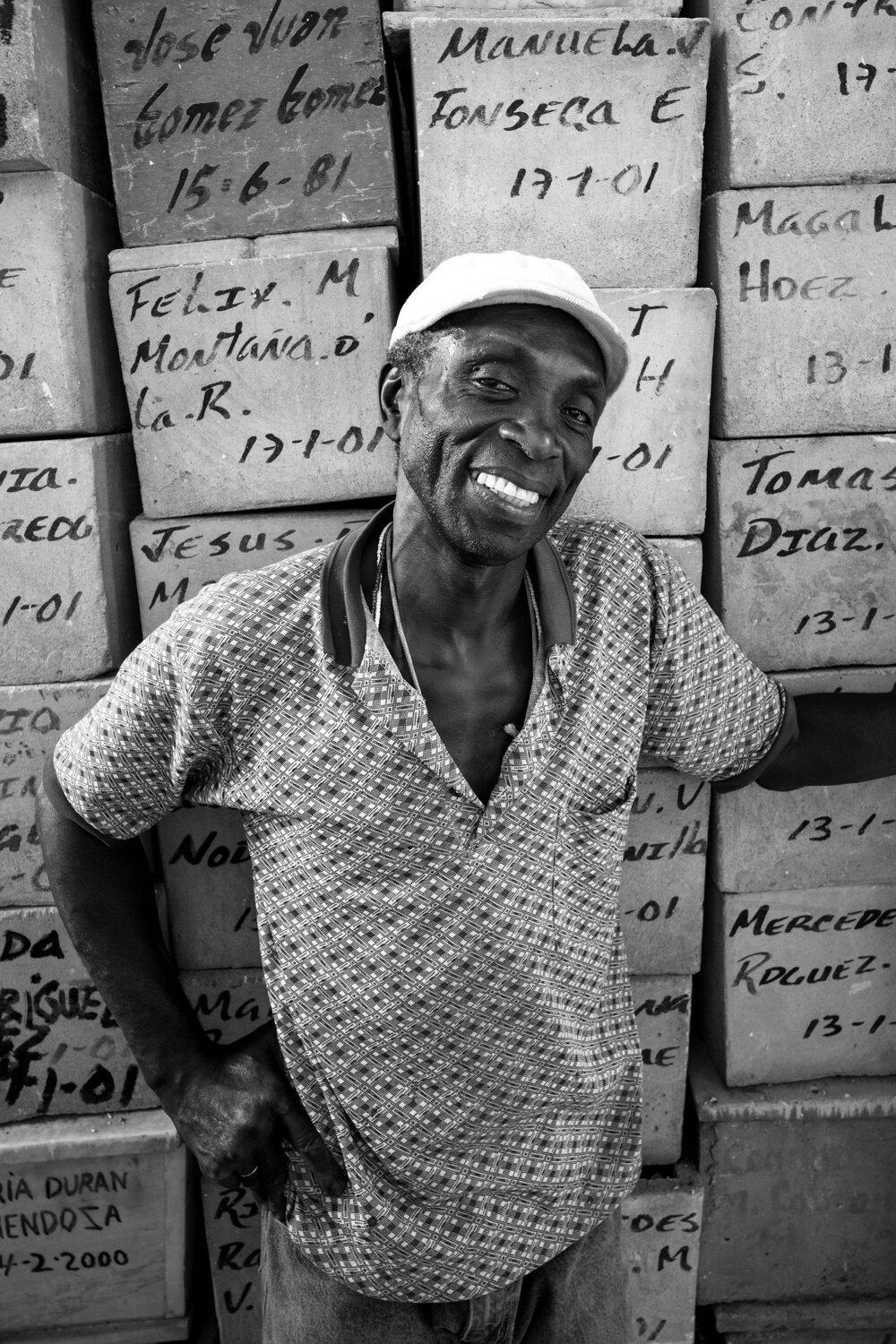

©Ayash Basu

Left: Sardiñas looks at the overhead skylight, his only source of natural light in the crypt while holding on to his precious torch.

Right: Sardiñas beams his trademark smile standing next to boxes stacked floor to ceiling, all organized and marked.

Yet, Sardiñas feels at home here and shows it with every ounce of his presence and charm. He shakes my hands, gives me a hug, and shows me around his space with such abundant gusto, a dose of which would go a long way in cheering up the “Beefeaters” guarding the Buckingham Palace. In terms of equipment to do his job, Sardiñas has a few rickety wooden ladders, some marker pens to write down names on boxes, and a torch, which he uses judiciously, given the severe difficulties of obtaining batteries in Cuba. In all seriousness, if asked what “workplace equipment” tops his wishlist, Sardiñas would likely point to AAA batteries.

©Ayash Basu

Left: The underground crypt stores thousands of boxes, each marked and arranged by date and family name.

Right: The crypt is dark and damp, a few skylights admit little light and this forms Sardiñas’s work place everyday.

I asked him if he never feels even the slightest sense of fear and distress doing what he does. Grinning ear to ear he replies, “It’s the living ones that scare me,” bursting into laughter at my incredulity as I imagine myself doing what he does. Sardiñas approaches his job as a flower gardener, carefully tending to each box and its contents, taking the effort to place boxes from the same family nearby each other, even if they come to the crypt years apart. His customer satisfaction scores must be through the roof, except that he hasn’t any — they all live in the past tense. Yet, to him, each box represents a soul with a story that must be nurtured.

©Ayash Basu. Sardiñas knows the place by heart, he quite literally has shaped it with his hands and proudly displays his organization skills.

After about an hour or so, I was at my wit’s end and decided to step outside. I’ve not been to the cemetery again, nor have I seen Carlos Sardiñas, but I have not forgotten him. I doubt I ever will. That evening at dinner, as I was sipping on a michelada at a local city café, I couldn’t help but notice the Dos Equis bottle that came with it. Jonathan Goldsmith may be the “most interesting man in the world,” but with each trip to the island, I ask myself if that “world” includes Cuba.